Two years of transnational discussions, pilots and development processes related with games are now compiled in a handbook. CONNEXT is proud to present: Games, seriously!? Serious games as a tool for empowerment handbook.

Games, seriously!? handbook summaries the gamification approach of CONNEXT and presents practical examples of game processes and game challenges carried out. Some questions discussed in the handbook include:

and presents practical examples of game processes and game challenges carried out. Some questions discussed in the handbook include:

- Why should one use games as a tool?

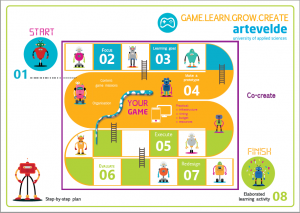

- What are the steps in game development?

- How does empowerment link with games?

- Why and how to involve participants in creating games?

- How can one use games to support inclusion and equality?

Co-writing served as an enriching and educational process for the authors of this handbook from Belgium, Finland and Sweden. We also discovered a new concept, which crystallizes what we have been doing all along: game-based empowerment. We have noticed in practice that games have an inspirational and engaging power. We are also convinced that they can be used to support youngsters and migrant groups in a meaningful way.

We now welcome you to read the handbook, become inspired and continue exploring game-based empowerment together with us!

Handbook Games, seriously!? Serious games as a tool for empowerment

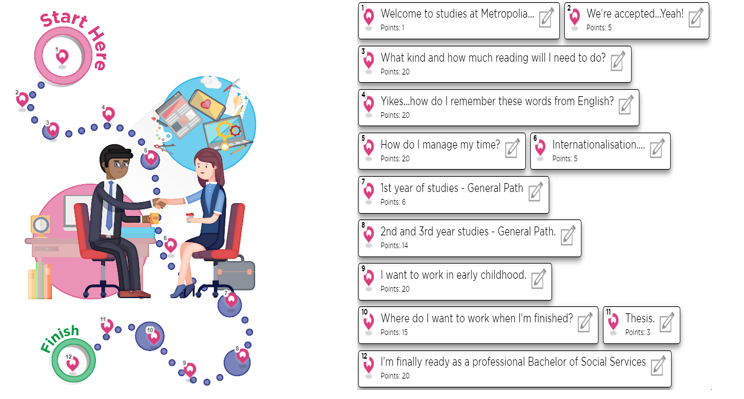

Psst! We have also published some CONNEXT game challenges on the website of Metropolia University of Applied Sciences and GameWise.io. Stay tuned, as there is more to come!

For a long time gaming was considered a useless and time-consuming activity for socially isolated nerds and geeks. However, professionals who use games in a learning context know better!

For a long time gaming was considered a useless and time-consuming activity for socially isolated nerds and geeks. However, professionals who use games in a learning context know better! In this game you’re stuck in your studenthouse during a lockdown. Get to know your housemates and learn how you can deal with difficult moments, stress, loneliness, anxiety and other taboos. Try gaining enough connection with all of your housemates to complete the game. This game was realised with the feedback and input of numerous youngsters and experts.

In this game you’re stuck in your studenthouse during a lockdown. Get to know your housemates and learn how you can deal with difficult moments, stress, loneliness, anxiety and other taboos. Try gaining enough connection with all of your housemates to complete the game. This game was realised with the feedback and input of numerous youngsters and experts.  In the meanwhile, CONNEXT Finland shared some of it’s game challenges online in order to inspire teachers, youth workers and other professionals working with youngsters to use gamification as a tool. For example Metropolia University of Applied Sciences compiled a game Keep well #isolation, which encourages participants to look around their own home and to identify tools, which can be used to support wellbeing. Another game, Ukko ylijumalan luontopeli (Nature Game of Supreme God Ukko), created by Helsinki Vocational College (Stadin ammatti- ja aikuisopisto) gave inspiration to start exploring outdoors. Practice+++ developed by YMCA Helsinki, encouraged youngsters to continue their volleyball exercises and physical activities on their own, despite the isolation.

In the meanwhile, CONNEXT Finland shared some of it’s game challenges online in order to inspire teachers, youth workers and other professionals working with youngsters to use gamification as a tool. For example Metropolia University of Applied Sciences compiled a game Keep well #isolation, which encourages participants to look around their own home and to identify tools, which can be used to support wellbeing. Another game, Ukko ylijumalan luontopeli (Nature Game of Supreme God Ukko), created by Helsinki Vocational College (Stadin ammatti- ja aikuisopisto) gave inspiration to start exploring outdoors. Practice+++ developed by YMCA Helsinki, encouraged youngsters to continue their volleyball exercises and physical activities on their own, despite the isolation.

Games are suited to everyone! When adjusting them to migrant groups, language support among other things needs to be highlighted. In CONNEXT we have worked around the topic internationally. This is a compilation of ideas on how to use gamification with migrants collected in a project partner meeting in Karlstad and in the CONNEXT Finland game sessions. Our game missions guide participants around their environment making use of different electronical platforms, but you can do yours in your preferred way!

Games are suited to everyone! When adjusting them to migrant groups, language support among other things needs to be highlighted. In CONNEXT we have worked around the topic internationally. This is a compilation of ideas on how to use gamification with migrants collected in a project partner meeting in Karlstad and in the CONNEXT Finland game sessions. Our game missions guide participants around their environment making use of different electronical platforms, but you can do yours in your preferred way!

Are you interested in how gamification supporting learning and empowerment has developed over the past years? What about how digital youth work has been done in Finland and how does it’s future look like? Virtual Gamified Diamonds Seminar was arranged to explore these questions and to have a gamified experience of the best ideas of CONNEXT for inclusion project e.g. on how to apply gamification in the following themes:

Are you interested in how gamification supporting learning and empowerment has developed over the past years? What about how digital youth work has been done in Finland and how does it’s future look like? Virtual Gamified Diamonds Seminar was arranged to explore these questions and to have a gamified experience of the best ideas of CONNEXT for inclusion project e.g. on how to apply gamification in the following themes:  Researcher Lobna Hassan (University of Tampere/Turku,

Researcher Lobna Hassan (University of Tampere/Turku,  Planner Juha Kiviniemi (

Planner Juha Kiviniemi ( Additionally, I looked into boys’ experiences of communication between family and school, the support they get from teachers and school curators, their own suggestions on how to improve this support as well as their own experience of participation and disadvantage in society. I interviewed boys and young men from 2 different schools and made use of the Capabilities Approach developed by Martha C. Nussbaum in the analyzing process.

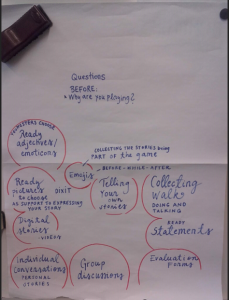

Additionally, I looked into boys’ experiences of communication between family and school, the support they get from teachers and school curators, their own suggestions on how to improve this support as well as their own experience of participation and disadvantage in society. I interviewed boys and young men from 2 different schools and made use of the Capabilities Approach developed by Martha C. Nussbaum in the analyzing process. MSC is a method based on collecting stories. It’s common for people to tell stories and to remember them. And it is a way of detecting unexpected changes.

MSC is a method based on collecting stories. It’s common for people to tell stories and to remember them. And it is a way of detecting unexpected changes.